When the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) expanded its land-based fur trade operations west of the Rockies to include coastal sailing craft, they introduced the first steamship to the West Coast.

As the SS Beaver was a coal-fired ship, the company became increasingly interested in finding coal resources on the northwest coast to replace cost-prohibitive imports from Britain.

The discovery of local coal would not only fuel the SS Beaver, but became the impetus for an expanding coal trade to external markets, the establishment of the Colony of Vancouver Island, and B.C.’s first labour strike asserted by Indigenous people.

The following year of 1836, the Beaver’s inaugural tour of the upper northwest coast visited these coal-bearing grounds. John Dunn verified the earlier Indigenous reports:

The cause of the discovery was as curious as the discovery itself was important. Several of the natives at Fort McLoughlin having, on coming to the fort for traffic, observed coal burning in the furnace of the blacksmiths; and in their natural spirit of curiosity made several enquiries about it; they were told it was the best kind of fuel; and that it was brought over the great salt lake – month’s journey. They looked surprised . . . The Indians explained, saying, that they had changed, in a great measure, their opinions of the white men, whom they thought endowed by the Great Spirit with the power of effecting great and unusual objects; as it was evident they were not then influenced by his wisdom, in bringing such a vast distance and at so much cost that black soft stone, which was in such abundance in their country.

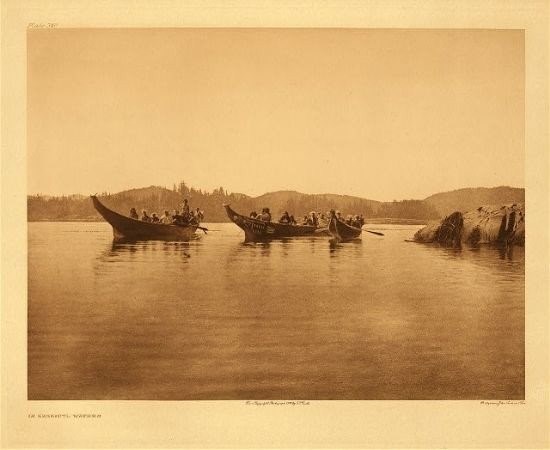

Dunn further stated that the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples subsequently delivered coal to the Beaver and “were anxious that we should employ them to work the coal; to this we consented, and agreed to give them a certain sum for every box. The natives being so numerous, and labour so cheap, for us to attempt to work the coal would have been madness.”

Duncan Finlayson, who accompanied Dunn, also confirmed the strong proprietorial stance of the Kwakwaka’wakw. “They informed us that they would not permit us to work the coals as they were valuable to them,” wrote Finlayson, “but that they would labour in the mine themselves and sell to us the produce of their exertions.”

These original coal fields described in 1836 were at Suquash, south of present-day Fort Rupert. Soon, considerations of whether to build a fort or “purchasing the mine” were discussed at both local and larger HBC corporate levels.

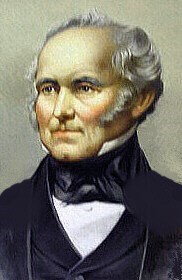

By October 14 1839, James Douglas, then an HBC Chief Trader, reported that about 100 tons of coal had been purchased from the Kwakwaka’wakw.

Through the 1840s, the HBC continued to discuss the possibility of establishing a fort, especially considering that other parties had become interested in the coal deposits – particularly the Royal Navy, which had yet to establish Esquimalt as its main base for the North Pacific squadron.

In later years, Vancouver Island coal was considered some of the very best in the British Empire. It was this coal that ultimately provided the additional incentive to colonize Vancouver Island.

By the spring of 1848, even private interests took notice. Samuel Cunard, of the well-known steamship lines, urged the British government to reserve the coal fields for the Crown.

Perhaps not realizing that the Oregon boundary settlement had secured Vancouver Island to the Crown, Cunard feared that “Individuals in the Oregon territory will be alive to the advantages resulting from the possession of this valuable article, and will endeavour to obtain the best situations, or acquire any right the natives may have, or suppose they have.”

Cunard continued such that immediate steps should be taken to “prevent the natives or others from acquiring or ceding rights to these mines.”

This information was subsequently forwarded to Lord Grey, Secretary of State for the Colonies. As a result, later that year in July of 1848, Captain George W.C. Courtenay wrote to Douglas (now HBC Chief Factor) with orders from Rear Admiral Hornby, Commander in Chief of British naval forces in the Pacific, to obtain further intelligence.

In a separate letter to Douglas, Courtenay enclosed a copy of the Cunard letter and “strongly recommend[ed] the Officers of the Honorable Company of Hudson’s Bay to keep a vigilant look out thereon.” Courtney continued “in the event of any persons settling near the Coal Mines or attempting to work them, either to cause their removal or serve them with notice to depart.”

“It would be desirable to take possession of that district for Her Majesty,” stated Courtenay, and “I am informed that the practice in these parts on taking possession of Land is to build a Hut thereon.”

In the Admiralty’s view, this was a means to assert occupation.

Courtenay’s inscription to be attached to the “Hut” read as follows:

These and the adjacent Lands together with the Coal and Minerals contained therein are taken possession of through the agency of the Honble. Hudson’s Bay Company by me George Courtenay, Esq. Captain of Her Britannic Majesty’s Ship Constance, acting on behalf of Rear Admiral Hornby, CB, Commander in Chief of Her Majesty’s Squadron in the Pacific, For Her Majesty Victoria Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, Her Heirs and Successors.

All persons are therefore warned not to settle thereon, or to visit these the said Lands for the purpose of working the Coal or other Mines.

God Save the Queen

Given onboard the Constance in Port Esquimalt the 17th August 1848.

The twelfth year of Her Majesty’s Reign

“signed” G.W.C. Courtenay

For his part, James Douglas was just returning from the Hawaiian Islands. Upon arrival he conveyed his impression of the Admiralty’s steps for the assertion of sovereignty in a letter to the HBC Governor and Committee:

“Captain Courtenay . . . has taken possession of the Coal mines of Vancouver’s Island, in behalf of the Crown, a measure recommended in a letter, bearing the signature of ‘S. Cunard’, to the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, to prevent the encroachments of American citizens, an alarm which appears groundless, as since the late Treaty no American Citizen can, by settlement, acquire any legal rights to the lands within the limits of British Oregon.”

Douglas was right. But with the Imperial government and Admiralty so interested in the island’s coal resources, the HBC through Douglas began to take the long-awaited steps of building the fort.

The Imperial government was increasingly determined to formally colonize Vancouver Island as the best means to control these strategic coal reserves.

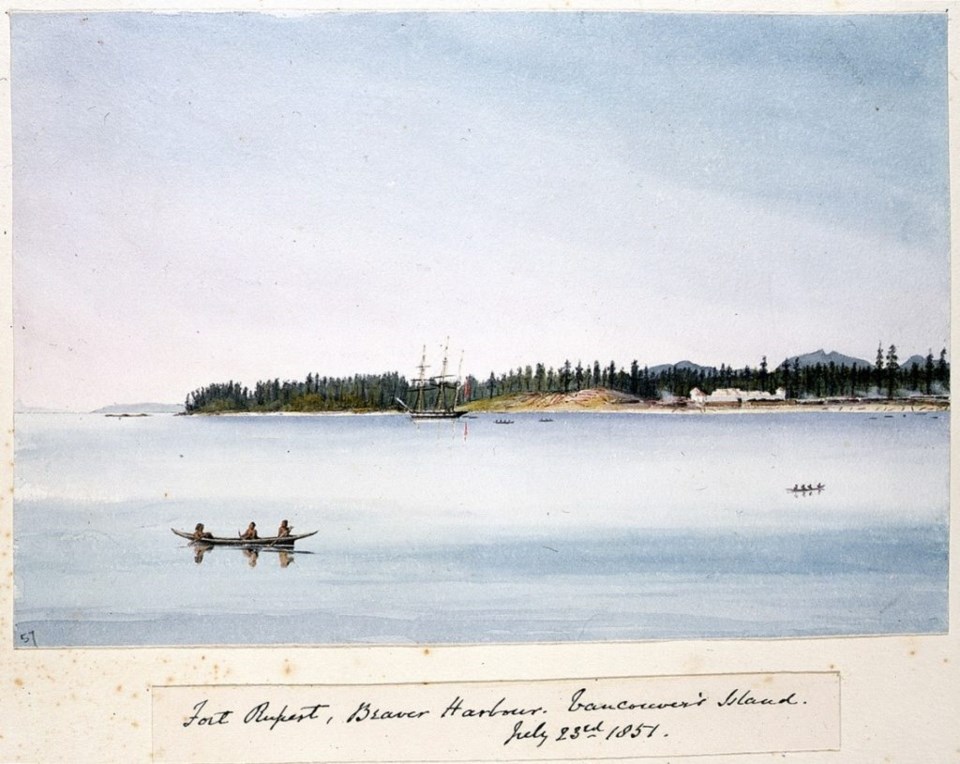

The Imperial gaze was about to bring the most far-flung of HBC operations into the bold light of colonial power. Not coincidentally, both Fort Rupert and the Colony of Vancouver Island were established in that same year, 1849.

There was one problem: there was no safe harbour in close proximity to these mines. Larger ships had to anchor upwards of two miles from the coast to receive the coal-ladened canoes of the Kwak'wala-speaking-peoples.

In 1849, the HBC decided upon Beaver Harbour with its deeper waters as a more practical port to locate the new fort.

The construction of Fort Rupert was an incredibly mixed-race project, with many employees relocated from HBC operations at Fort Stikine. In addition to the usual Scottish, French Canadien, and Metis employees, there were also Hawaiians, Russians, and Tlingit wives, including four tribes of Kwak’wala speakers numbering upwards of 1,200.

While these HBC employees concerned themselves primarily with the fort’s construction, the Kwakwaka’wakw continued to mine coal from surface deposits at Suquash, transporting it in canoes along the east coast of Vancouver Island to Fort Rupert, in addition to assisting with construction.

This arrangement changed with the arrival of professional coal miners from Britain, contracted by the HBC to further investigate coal fields in the region – in many instances working alongside the Kwakwaka’wakw.

As the HBC entered Beaver Harbour to build the fort, George Blenskinsop entered into the post diary that the “Indians appear friendly and well pleased at our coming to establish amongst them, and have so far done all in their power to assist us.”

Blenkinsop also noted “it is but justice to say they [the Kwakwaka’wakw] work uncommonly well and appear uncommonly friendly.”

By late fall, apparently at times as many as 100 Kwakwaka’wakw were working for the establishment (independent of the Suquash coal mines), but in short order once-friendly relations became stressed. The newly-arrived British miners essentially broke the Kwakwaka’wakw labour monopoly asserted back in 1836.

With the introduction of foreign miners, Blenkinsop recorded within the pages of the Fort Rupert post journal the first-ever labour strike in what is now British Columbia:

“Indians today refuse to work till more pay is given.”

With coal shafts now being sunk in the interior reaches of the Island, in consequence of the poor and repeated test results along the coast, a new understanding was required for both the HBC and Kwakwaka’wakw.

Ultimately, the HBC was forced to soothe this ongoing labour strife by concluding the Fort Rupert Treaties – the only two such Treaties on northern Vancouver Island. But that’s a story for another day!

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.