When I was young, I traveled with my grandparents to Comox on Vancouver Island to take the ferry to the Mainland for a short camping excursion.

We were all excited to go, but then the weather changed – a fierce rain and windstorm – and like so many times this winter, the ferry was shut down to “the Continent.”

My grandfather was so very disappointed. “Damn it all!” he complained, “They should never have blasted Ripple Rock to oblivion – we could have had a bridge to this Island!”

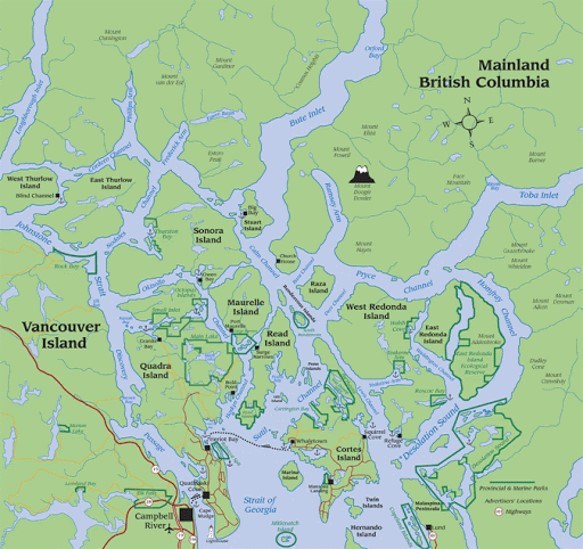

I had never heard of Ripple Rock before. As the old boy told me, the rock was located near Campbell River, and the fearsome whirlpool it created had taken down many a ship – and more than 100 lives. A navigational hazard, it was removed in 1958 with what was then the world’s largest non-atomic blast!

Old Gramps, puffing away on his pipe excitedly, thought it was a conspiracy by the Steamship Company – they wanted to make “damn sure” that a bridge to Vancouver Island would never be built. The immense rock submerged in the middle of Johnstone Strait was viewed as the key pillar-point to support a lengthy bridge span to Vancouver Island.

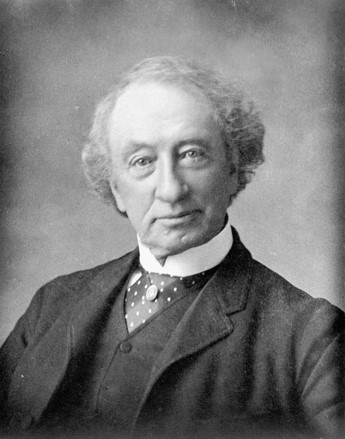

Ever since, I have been fascinated to learn more about this once proposed fixed-link to Canada, the now defunct Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway (what a shame!). Both were part of the same grand vision of connecting the Island with the "ribbons of steel" promise of John A. Macdonald's national dream.

It had generally been accepted by historians that the present-day Fraser Canyon Route of the transcontinental railway was the only practicable line. But this ignored a technically superior route via Bute Inlet that – although supported by a majority of members of the BC Legislative Council – was dropped by the federal government in favour of today’s Fraser Canyon Route.

Ever since, the Bute Inlet Route has been relegated to an inferior position and Prime Minister Macdonald’s original support for Bute Inlet and Esquimalt Terminus is seen today as a mere political ruse.

It was not always so. Bute Inlet No. 6 and Burrard Inlet No. 2 were once viewed as the “great rival routes” for connecting the new province with Canada. Under the Terms of Union, 20 July 1871, the federal government committed itself to the construction of a transcontinental rail link to the Pacific Slope.

As I have written, the Terms of Union contract with Canada was written in such a way that final decisions on divisive issues were effectively postponed.

Perhaps this kind of procrastination was typical of the “Old Tomorrow” tactics of John A. Macdonald. In the case of railways, Article 11 of the Terms of Union seemingly allowed all regions of British Columbia to believe they were destined for commercial greatness. The spoils of railway development quietly assured by shrewd Canadian agents who began plotting rail corridors throughout the province. In total, 21 survey parties were deployed from Ottawa to the Pacific Coast.

A practicable line that descended the Thompson and Fraser rivers was discovered in 1871 – through “imperfect exploration” – yet as Chief Engineer Sanford Fleming first declared, “the difficulties . . . appeared so great that a recommendation to adopt the route discovered, could not be justified until every effort had been exhausted.”

Survey operations were subsequently reorganized in 1872 to look beyond the immediate choice of the Thompson and Fraser rivers corridor.

The Canadian government surveys of 1871, which focused primarily on routes to Burrard Inlet, caused considerable consternation on Vancouver Island, especially in Victoria and Esquimalt. Many believed their favoured route of Bute Inlet, across Johnston Straits and the treacherous Ripple Rock of Seymour Narrows, had been entirely ignored.

As such, in 1872 the Canadian government sent three survey parties to Bute Inlet and the Valdez Group of Islands that was the only possible site for a fixed rail connection between Vancouver Island and the continent.

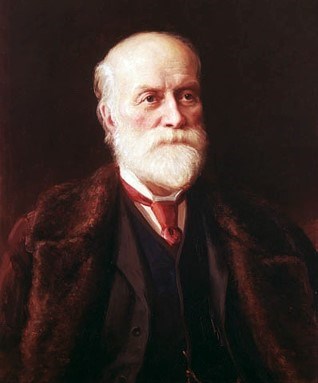

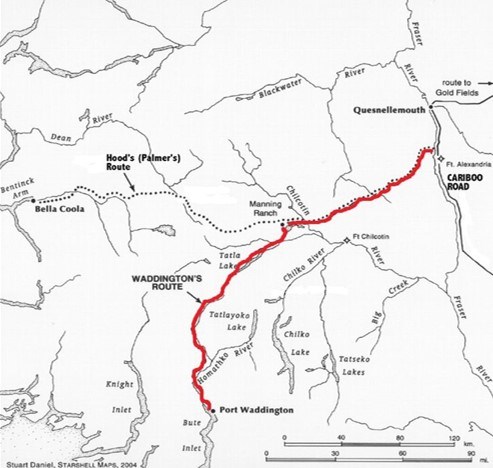

The extremely able engineer Marcus Smith, formerly with the Intercolonial Railway (whose diaries are held by the BC Archives) was sent to supervise all survey parties in the province. As the Deputy Engineer-in-Chief to Sanford Fleming and Resident Engineer for British Columbia, Smith (second cousin of economist Adam Smith) took an immediate interest in the Bute Inlet route. The Canadian government had purchased the plans of former road builder Alfred Waddington that outlined a route from the head of Bute Inlet in Homalco (K'ómoks) country (the undeveloped town site of Waddington), up the Homathko River and ultimately across the Cascades through Tŝilhqot'in traditional territory to the Cariboo gold fields.

Waddington’s earlier attempt to construct a bridal trail along the steep banks of the Homathko Canyon was roundly condemned by lower Mainland authorities, who realized that any such success would have usurped the wealth of the Cariboo to Victoria, and away from the Fraser Canyon and New Westminster. The Canadian government was not deterred and supplied Marcus Smith with copies of Waddington’s reports for 1862. Of course, this was the earlier colonial roadbuilding project that had sparked the infamous Chilcotin War.

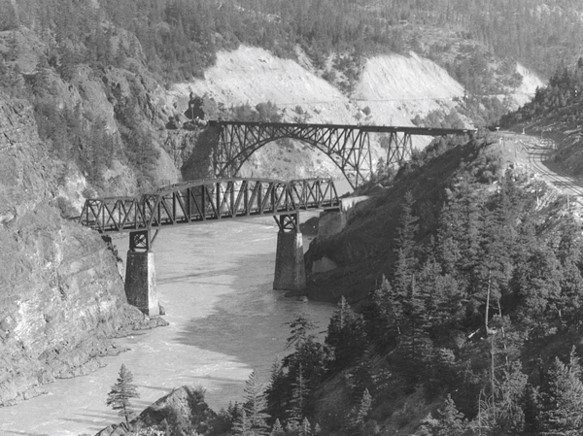

Smith considered Waddington’s prior work both arduous and “honestly prepared.” After further inspection, a practicable route was located by survey crews as early as 1872. In addition, a further survey continued from the north side of Bute Inlet to the Valdez Group of islands and crossed a selection of sea channels, including Seymour Narrows, to a point on Vancouver Island just north of today’s Campbell River. The line was not an easy trek, but nevertheless one of the first established as a possible western section of the “all-red route.”

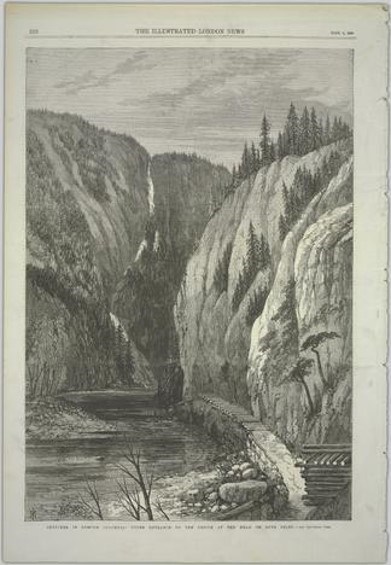

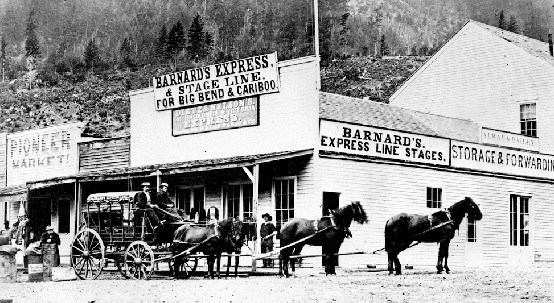

By contrast, on July 21 1872, Marcus Smith jotted down in his field diary, a rather cursory, yet seemingly condemnatory, opinion of the Fraser and Thompson river canyons as possible rail corridors. In a kind of staccato-like hand, the diary held by the BC Archives records:

Started at 3 p.m. in Barnard’s [express] stage. [D]rove through the Canon. [M]iles to Boston Bar very rough and wild and unfavourable for a railway . . . . up the fraser still very rough road. [A]t summit Jack ass mountain said to be 1200 feet above water and nearly perpendicular. [On Thompson River] the banks being gravel, sand or loam and subject to slides – very unfavourable for a railway – more so even than the rocky Canon of the Fraser.

Curiously, these negative references were not subsequently included in a transcribed diary for public consumption. One can only assume that such remarks would have infuriated certain Mainland interests – particularly those of New Westminster and Yale – so discretion was perhaps advisable.

At the end of 1873, there were seven projected routes, all still at the exploratory stage. Yet of these seven, only two were given real attention by an anxiously awaiting public: Burrard Inlet No. 2 and Bute Inlet No. 6.

Both had formidable problems – but the problems associated with Bute Inlet were known and calculated (unlike the Fraser Route), as it had been surveyed instrumentally. As such, Bute Inlet No. 6 presented the only favourable course in 1873. The extension of this route to Vancouver Island, however, was much more formidable, an island-hopping 30-mile long fixed-link calling for seven clear-span bridges over water channels in Johnston Straits.

Sanford Fleming believed that the magnitude of such construction was “not only formidable, but without precedent.” Nevertheless, on this basis, Prime Minister Macdonald confirmed Esquimalt as the Western Terminus by Order-in-Council.

Contrary to public opinion, railway suspension bridge technology was well established by 1873. This is not to discount the obvious engineering difficulty of such a massive project, but to affirm that the preeminent factor raised against bridging the straits was cost, not technical feasibility. Indeed, the reason CPR surveys were extended beyond 1871 to areas such as Bute Inlet was the enormous cost of rail construction in the Fraser Canyon route.

Along with officially naming Esquimalt the terminus was Canada’s request to appropriate a railway belt along the east coast of Vancouver Island all the way to Seymour Narrows – what is today the vast Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway land grant which still holds the subsurface rights of all private property land owners.

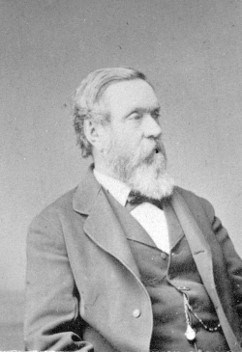

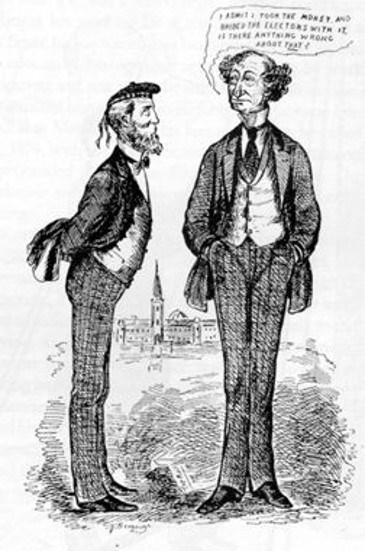

The Macdonald policy quite clearly committed itself to Bute Inlet, the Island railway to Esquimalt, and ultimately the Seymour Narrows bridging scheme. But with the “Pacific Scandal,” Macdonald’s government was thrown from office and Liberal leader Alexander Mackenzie came to power – a bad omen for supporters of the Bute Inlet route. Mackenzie’s Minister of Justice, Edward Blake, would soon refer to BC in the Canadian Parliament as “an inhospitable country, a sea of sterile mountains.”

In a Privy Council Report, 13 March 1876, the Liberal government enunciated succinctly the prior Conservative Party position:

By this policy, had it remained unreserved, the [Liberal] Government would have been obliged to provide construction of over 160 miles of railway on Vancouver Island, at a probable cost of over seven million five hundred dollars; besides the building of a railway from the head of Bute Inlet and the bridging of the Narrows, a work supposed to be the most gigantic of its kind ever suggested, and estimated to cost over twenty-seven million and a half dollars.

Unquestionably, Macdonald’s promises amounted to politics; balancing the sectional interests of the Island and Lower Mainland. Yet an overly cynical view is not necessarily in order.

Others, like Amor De Cosmos, perhaps predictably, believed the transcontinental line should have been treated as an Imperial concern with, presumably, Imperial financing to allow for the much larger work. As federal member for Victoria City “he took it that this Government would make a very great mistake indeed if, for the paltry consideration of a few millions of dollars to-day, it should select the wrong route.”

Work continued on these competing lines, as did the “Battle of the Routes” – the competing regional interests remaining ever vigilant. In June 1874, Marcus Smith embarked upon a pleasure trip to Seymour Narrows and adjacent islands in the company of James Douglas Jr. (the former governor’s son), and other notables such as Chief Justice Matthew Begbie. As far as the Resident Engineer was concerned, on the basis of “what we saw yesterday I have no expectation that a line any better than that of Bute Inlet can be had.”

James Douglas, Jr., later an MLA – and intimately connected to the interests of Victoria – obviously agreed. He judged the Fraser River Route to be a “tortuous” and “narrow rocky defile.” After having perused Fleming’s report for 1874, the former governor’s son remarked that “We may consider this opinion as sealing not only the fate of the [southern] routes, but the doom of New Westminster and Burrard Inlet as the Pacific terminus.”

By 1876, the trial location survey was finished the entire distance from Yellow Head Pass to Waddington Harbour. Route No. 6 – not the Fraser River line – became the first fully staked-out course for a railway in British Columbia. In doing so, it elevated the Bute Inlet Route to a more formal status above all other routes in British Columbia that were still at the exploratory or instrumental stage.

By then, five years had passed since union with Canada and still no signs of actual railway construction. The new province had become increasingly irritated by Canada’s slow progress in fulfilling Article Eleven of the Terms of Union. Secessionist pressure demanded that a decision be made soon.

Consequently, further exploration and surveys were finally halted in favour of evaluating completed surveys. Eleven individual lines were now assessed for their unique engineering features and the commercial traffic they would have to sustain if chosen.

Federal authorities, however, in comparing the advantages and disadvantages, were charged with a very difficult, if not impossible, task. Sufficient data was available for only one route – that of Bute Inlet No. 6 – so that in most instances this line served as the only real basis for comparison to all other routes. Perhaps this illustrated the faith that many administrators had in the Bute Inlet line!

Times were changing politically. Chief Engineer Fleming ultimately overruled his second in command, Marcus Smith – and without any comparable data for other competing routes – confidently asserted that “there can scarcely be a doubt as to Route No. 2, terminating at Burrard Inlet, being the best.” Odd, considering little comparable evidence had been established for the Fraser River corridor.

Why is this? Part II of the “Battle of the Routes” will provide the answer to this great untold story – a story that had it gone differently, would have produced a human geography and settlement pattern in this province unrecognizable today.

“Hey Gramps, aren’t you glad they blew up Ripple Rock?”

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall wrapped up his epic three-part series looking back at the negotiations between BC and Canada - and the unresolved issues that plague us to this very day.

- Rejean Beaulieu reconsiders the crucial role - and original location - of Fort Langley.

- Daniel Marshall on the "third great devil dance" in North America.