Prior to Confederation with Canada in 1871, British Columbia was part of a natural north-south world west of the Rocky Mountains. I have always been fascinated by this pre-provincial period, and particularly the many historic connections between BC and California and the gold rush populations that once freely traveled up and down the Pacific coast.

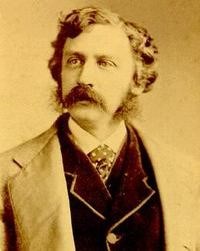

One of the great storytellers of the British Columbia and California goldseeking era was Halifax-born newspaperman David W. Higgins, who joined the Fraser River gold rush of 1858 from San Francisco during the height of the rush north.

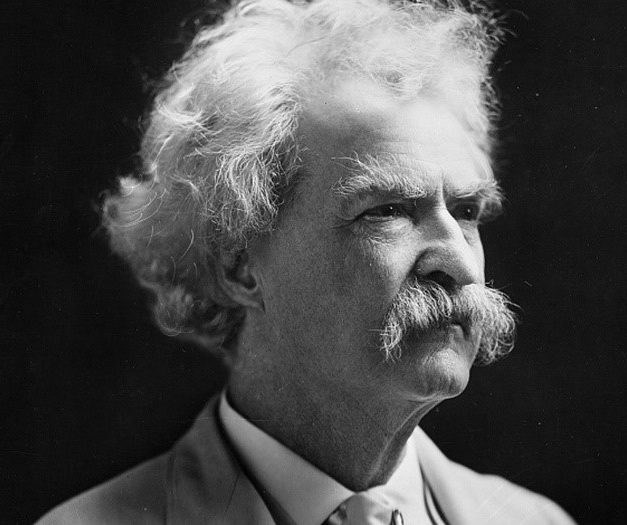

The Higgins family had traveled to New York where he was educated and subsequently apprenticed as a journeyman printer. By 1856 the lure of California gold saw his relocation to the Golden State where Higgins became the joint proprietor and editor of the San Francisco Morning Call newspaper that later employed Mark Twain as the paper’s Nevada correspondent.

Before Twain had commenced reporting for the Morning Call, Higgins had already departed for the New El Dorado of the north, establishing a store in the 1858 gold rush epicentre of Yale, BC, along with an agency for Billy Ballou’s Express Company. He remained there for a little under two years before relocating to Victoria, where he became the editor of the British Colonist newspaper and a career in early provincial politics that included nine years as Speaker of the Legislature.

“During the half century that I was in active life,” wrote Higgins, “I made copious notes of events as they transpired. I carefully studied the peculiarities of speech, the habits and mode of life, and the frailties as well as the virtues of the early gold-seekers on the Pacific Coast.”

Higgins subsequently authored two volumes of reminiscences, The Mystic Spring and other tales of western life (1904) and The Passing of a Race and more tales of western life (1905) concerned primarily with the transnational gold seeking populations of the Pacific Slope. The books were well received, with one influential journal declaring that “Mr. Higgins has done for Victoria and British Columbia what Bret Harte did for the Western United States mining districts.”

Like Twain and Harte – an American short-story writer who featured miners, gamblers, and other romantic figures of the California Gold Rush – Higgins sought to capture the life of gold rush communities “who peopled the Pacific Coast” and the “peculiarities that have engrafted themselves upon society of the present day, and may ever remain prominent features of life. . . in California and the British Pacific.”

Think of gold rush parlance still used today: paystreaks, “flash-in-the-pan,” motherlode, striking it rich, staking a claim, and so forth.

Without a doubt, writers such as Twain and Harte (who was seen camped out at Point Roberts during the 1858 rush), did more to popularize stories of the California mining frontier than most others of their time. British Columbia has its own equivalent: David W. Higgins’ short stories of gold rush life. How appropriate; this was deemed by many to be British California! Here is one of Higgins’ intriguing stories from his time in Yale, entitled A Child that Found Its Father. The curious story of Harry Collins, whom Higgins met, befriended, and employed subsequently in his Yale store.

Higgins called it “one of the strangest experiences in my life.”

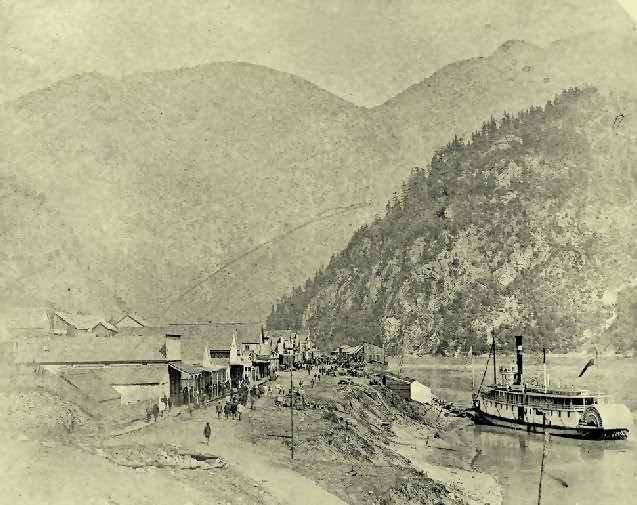

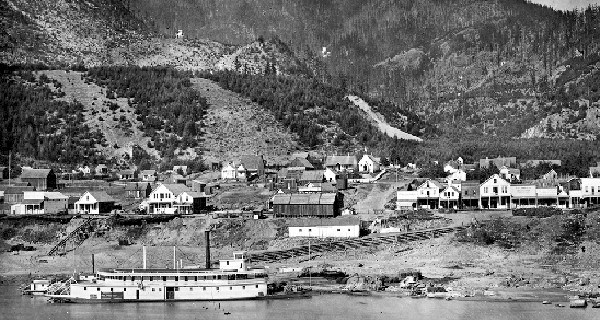

To the thousands of gold seekers, gamblers, and card sharks roaming the banks of the Fraser in 1858, Harry Collins – a recent arrival from San Francisco – was a slightly-built, pleasant young man. He was looking for his older brother George, who had a mining claim somewhere on one of the many gold rush bars (sand & gravel bars) along the Fraser River.

Higgins recalled how he had traveled by steamer from Victoria to Yale along with the young Collins lad who was in a seemingly destitute state:

We reached Yale before dark and landed at once. I am sorry to say that I forgot all about Collins . . . and I went to my own quarters back of the express office. . . The next morning, while writing at my desk, I heard a footstep, and looking up saw my fellow passenger of the day before. He looked wan and ill, and black half circles under his eyes gave evidence of great weariness, if not want of sleep.

‘Are there any letters for Harry Collins?’ he asked, timidly. ‘None,’ replied Vann [Higgins’ assistant]. ‘Any for George Collins?’ The same answer was returned, and he was walking slowly away when I arose and asked him where he was staying in town? ‘Nowhere,’ he replied.

‘Nowhere!’ I exclaimed. ‘Do you mean to say – where did you stay last night?’

‘I didn’t stay anywhere. I just walked back and forth between here and the Indian village.’

‘Good gracious, man,’ I cried, ‘why did you not knock me up? I’d given you a place to sleep.’

Higgins subsequently took the young Collins under his wing providing him food, lodgings and employment on his mining claim at Fort Yale Bar. During one of Higgins’ inspections of his claim on the foreshore of Yale, he quickly saw the young man was not particularly suited to the hard rigours of mining life.

There I saw Collins standing on top of a long range of sluice boxes, armed with a sluice fork, engaged in clearing the riffles of large stones and sticks which, unless removed, would obstruct passage of the water and gravel and prevent capture of the tiny specks of gold by the quicksilver with which the rifles were charged.

On the way I met the foreman. He was in a white rage because I had sent a ‘counter-jumper,’ a mere whipper-snapper, down to do a miner’s work. He tried him at the shovel and pick, and he was too weak to handle them, and so he had put him at the lightest of job on the sluices. ‘He won’t take off his coat like the other boys, and all the men are threatening to strike because they have to do harder work for the same pay that he’s getting. There he stands, with his long duster flapping in the wind. Like a pillow-case on a clothesline,’ concluded the foreman with a look of disgust on his face.

‘Never mind, Bill,’ said I, ‘you won’t be troubled with him anymore. I have a better job for him.’

Higgins promptly installed young Collins in his Yale store where he “proved to be an excellent cook, as neat as any housewife, and a fairly good bookkeeper.”

His employment continued for about four months, each evening after his duties Collins “would sit on a box in front of the store and listen to the wonderful tales of gold finds as they were narrated by miners and prospectors.” But through it all Harry continued to be preoccupied with finding his long-lost brother, who it was assumed must be somewhere in the upper goldfields. Higgins recalled:

Of every miner who came into the office from above the canyon Collins made anxious inquiries about his brother. Did they know him by name, or had they met anyone who answered to the description which he gave them? The answers were always in the negative, but he never despaired and every failure seemed only to incite him to renewed inquiries.

As Higgins became increasingly preoccupied with finding Harry’s brother he also confessed to having become “strongly and unaccountably drawn towards him.”

A strange emotion stirred in my heart and a wave of tenderness such as I had never before experienced swept through every fibre of my being. What ails me? I asked myself. . . Why should I be attracted towards him more than to any other young man? Why was I always happy when he was near and depressed when he was absent? Why did I lie awake at night trying to work out some plan to send word to his brother? Why did the sound of his voice or his footstep send the hot young blood bounding through my veins? What was he to me that every sense should thrill, and my heart beat wildly at his approach?

The mystery of Harry Collins would soon be answered for David Higgins. One day in 1859, after staying four months at the Yale Express Office, Harry was taken ill and Dr. Fifer – the local medical physician – was called to attend. After inspecting the patient, Fifer emerged from a back room in the office to report his findings to an anxious Higgins.

‘It’s my duty to tell you that Harry Collins is no more!’

‘Mercy!’ I cried, shrinking back, ‘Not dead? Not dead?’

“Well, no, not dead; but you’ll never see him again.’

‘If he is not dead,’ I said greatly agitated, ‘tell me what has happened or why I shall never see him again. You should not keep me in suspense.’

‘Well,” said the doctor, laughing heartily, ‘he is not dead. He is very much alive. Harry Collins is gone, but in his place there is a comely young woman who calls herself Harriet Collins, the wife of one George Collins, who is now above the canyon hunting for gold.’

“Harry” was really Harriett Collins: a young, pregnant wife from San Francisco searching for her husband in the chaos of the Fraser River gold fields. Disguised as a man for safety, she looked for her husband, George, amidst the rowdy mining town of Yale.

The two were shortly reunited when George returned to Yale. Their baby daughter was subsequently named Caledonia H. Collins, honoring both the location of her birth (British Columbia was previously called New Caledonia) and the H. standing for Higgins in recognition of her host’s kind hospitality. The fact that Harriet felt compelled to masquerade as a male during her trip north, and subsequent four-month stay in Yale, is suggestive of the chaotic, male-dominated world this young woman was compelled to travel through.

The reunited couple along with their baby daughter soon left for California never to be seen again, but for one last communication received by Higgins from San Francisco:

Some weeks after Mr. and Mrs. Collins had gone away, engraved cards for the christening at San Francisco of a mite to be named Caledonia H. Collins were received by nearly everyone in Yale. Mine was accompanied by an explanatory note that the ‘H’ stood for my surname, and that I was to be the godfather. . . Nine years sped away before I was enabled to visit San Francisco, and diligent enquiries failed to discover any trace of the Collins family. They had moved away from the city, and I never since heard of or from them. Somewhere on the face of this globe there should be a mature female who rejoices in the name of Caledonia H. Collins. If these lines should meet her eye I would be glad to learn her whereabouts, for I would travel many miles to meet the woman who under such extraordinary circumstances became my god-daughter.

Higgins never again met Harriet, George or Caledonia Collins, but perhaps one day a genealogist will discover their whereabouts!

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall concluded his series on war in the new El Dorado and the making of modern BC.

- Rick Cluff sat down with Daniel and talked about his love of BC's unique history.

- Michael Layland on the arrival of HMS Topaze in Esquimalt, and the naturalist onboard who would literally write the book on Vancouver Island wildlife.