As a gold rush historian, I have always been fascinated by the immense excitement and profound mania that swept through mid-19th century gold seekers in California, Australia, and British Columbia. In the 1849 California rush it was referred to as “Gold Fever,” the “California Fever,” the “Yellow Fever,” and “Gold Mania.”

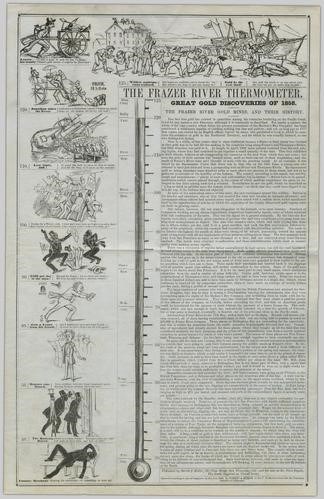

In the Ancient Greek the word mania (μανία) means quite simply madness or frenzy. The Fraser River gold rush of 1858 – considered the third great mass migration of gold seekers in search of a New El Dorado – was no different.

The Californian historian Hubert Howe Bancroft in his late 19-century history of BC wrote of “the infection which spread with such swift virulence in every direction” – an absolute mania that had gripped the Golden State – “the third great devil-dance of the nations within the decade” following the Californian (1849) and Australian (1852) gold rushes.

“At one leap British Columbia had become the rival if not the peer of California herself,” concluded Bancroft.

“Never, perhaps, was there so large an immigration in so short a space of time into so small a place,” wrote The Reverend R.C. Lundin-Brown. Many in California felt that the delirium was reminiscent, if not exceeding, that of the old glory days of ’49, so missed by thousands of old sourdoughs who had been left behind in the wake of capital-and-labour intensive mining developments.

“The desire to become rich suddenly . . . . [had] spread like an epidemic throughout the state,” alerted the San Francisco Bulletin. Abraham Lincoln’s future secretary of war, Edwin Stanton declared, “A marvellous thing is now going on here . . . [that] will prove one of the most important events on the Globe.”

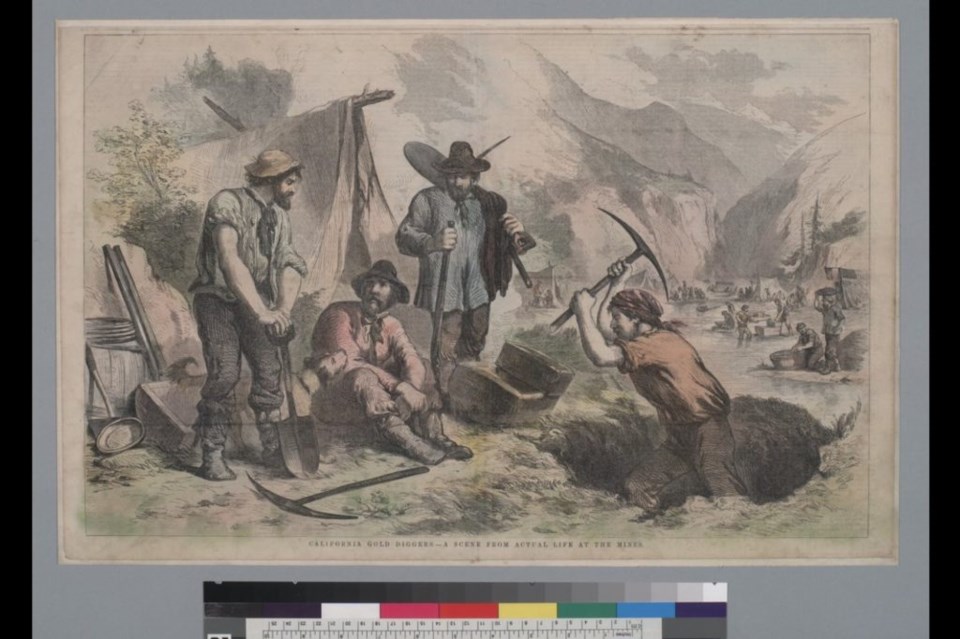

Stanton was not the only American swept up by the excitement of the Fraser River gold rush. Wild suspense continued to build about the “New Yellow Fever” noted the Bulletin, as “knots of old experienced miners, verdant new-comers, excited youths, wild spectators, with a sprinkling of ‘Micawbers’ and bummers, were seen . . . discussing the chances of accumulating a ‘pile’ by a few months of hard toil.”

Nor was the general panic created by BC gold limited to San Francisco. The interior gold camps of California, hundreds of them dotted along the Sacramento, Yuba, and Feather rivers, were on the march by the middle of May 1858.

“In the stage, from Murphy’s to Stockton, little else was talked about yesterday,” exclaimed an excited gold seeker. “And every time the persons inside (several of whom were old miners) passed acquaintances on the way, they were saluted with, ‘Halloa, John, (or Tom), on your way to Frazer River?’”

The general impression [reported the Bulletin] when a man was seen travelling, he must be on the route to the new mines. At Oroville, Marysville, and Sacramento, 10,000 miners were reported as preparing to leave. The San Francisco Newsletter believed that at least 50,000 would join the rush within 90 days. “These figures are not written at random,” the Newsletter claimed, “but from positive information obtained from the interior of the northern, central and southern sections of this State.”

Californians were not only pouring in, but staying. And the few that did return apparently had “a good deal of gold to exhibit,” which was likened to “oil upon the fire already lighted.”

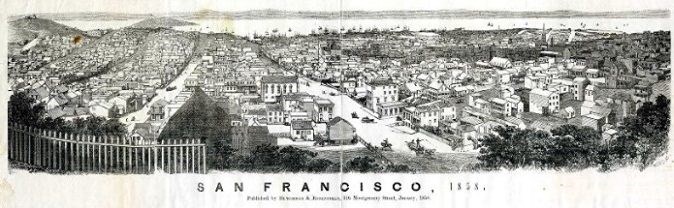

The result was instantaneous. The Fraser River goldfields were a reality and, according to newspapers of the day, they “created a much more general and violent excitement” than had ever been experienced in the Eastern States during the days of ’49. “Excitement of this kind is infectious,” wrote the Bulletin’s editor, and “A person who does not run out and listen to the talk on the streets, in the bar-rooms, in business stores . . . can have no idea of the alarming state of the Frazer river excitement at the present moment in San Francisco.”

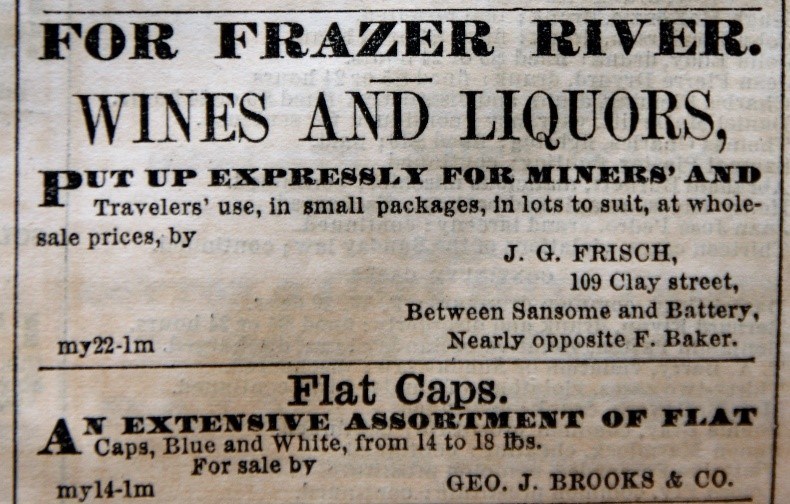

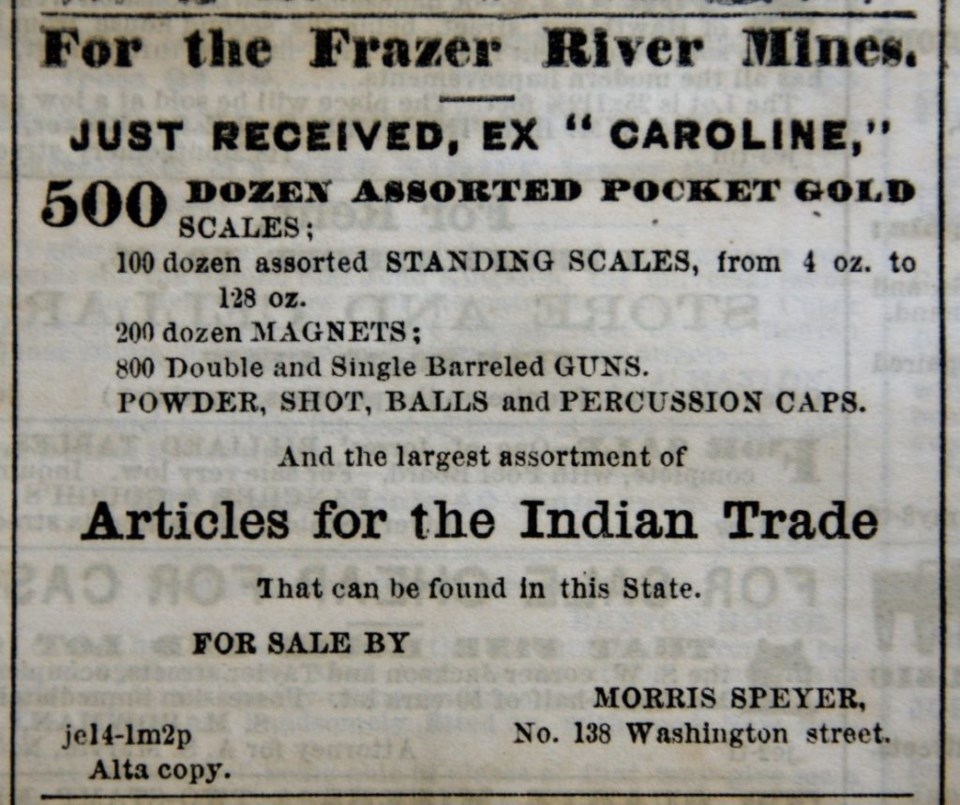

Certainly the San Francisco business community understood the “alarming” state of things and made the most of it. Whisky, wine, beer, pork, picks, pans, shovels, gold scales, boots, books, packs, maps, medicines, and miracle cures were all re-packaged for special use on the Fraser River.

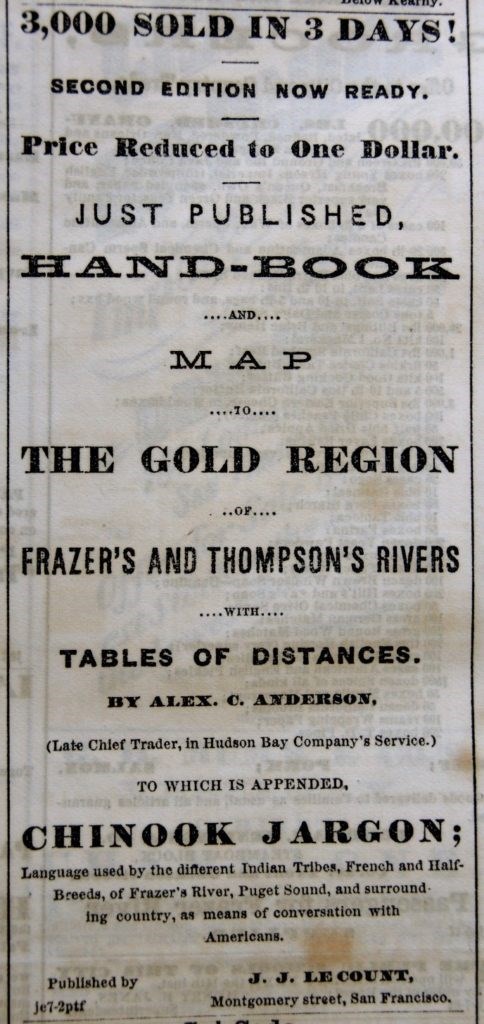

Charts were immediately offered for sale of varying quality, accuracy, and technical detail. A. C Anderson’s Handbook and Map to the Gold Fields (1858) would sell an unprecedented 3,000 copies in just three days!

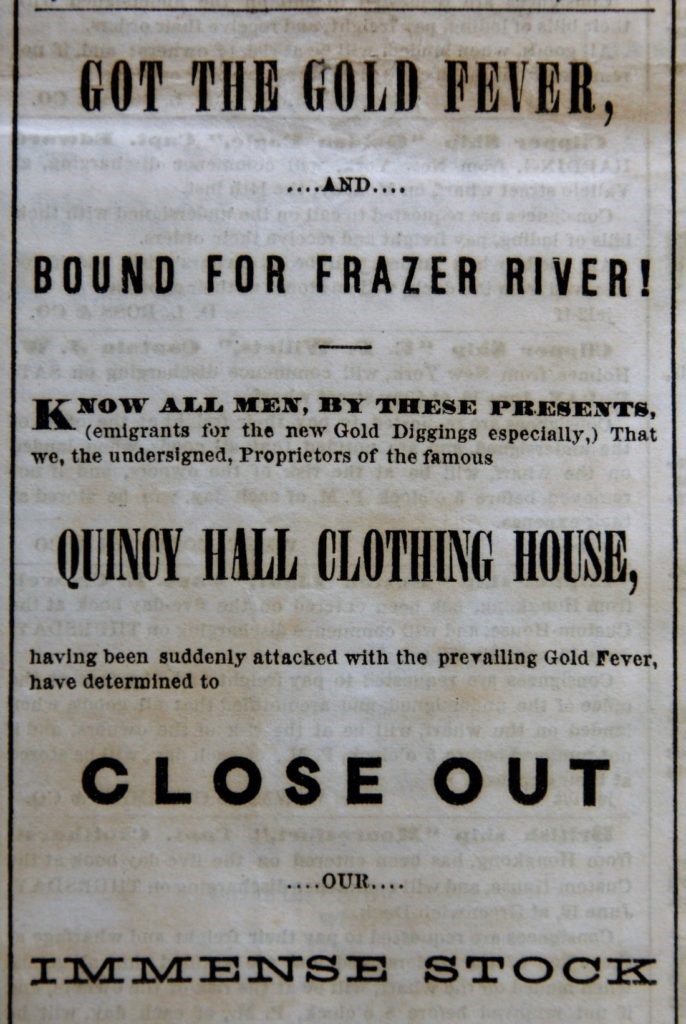

Warm woolens refashioned for the Fraser River’s northern climate became the selling card of many a clothier: “We have a large stock of heavy and coarse Coats, Pea-jackets, Pants, Shirts, Socks, &c, just suitable for . . . miners visiting those mines.” The Quincy Hall Clothing House proclaimed in large, bold type that it was closing out its immense stock: “GOT THE GOLD FEVER AND BOUND FOR FRAZER RIVER!” Grocery stores warned of the scarcity of provisions up north and suggested that miners bound for the Fraser River stock-up with supplies before departing.

Merchants, such as Thomas Hibben, were even more determined to capture the full extent of the new trade. Hibben quickly dissolved his partnership in the “Noisy Carriers’ Book & Stationary Company” to relocate to Victoria.

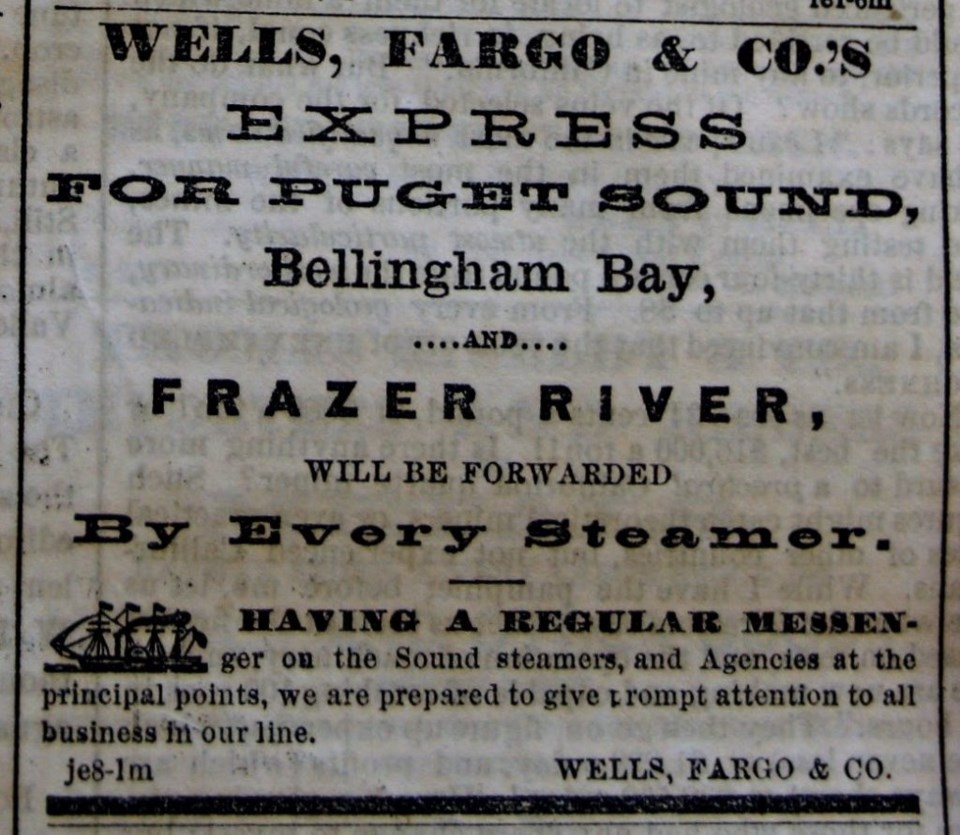

Wells, Fargo and Company also established an express headquarters in Victoria, while “Nichols & Co.’s Express for Frazer River” would be just one of several smaller mail carriers to notify Californians of their intended move north.

Even the San Francisco Bulletin would print a timely run of “The Bulletin for The North,” which had as a special feature an extensive, very useful listing of Chinook Jargon with equivalent translations in both English and French.

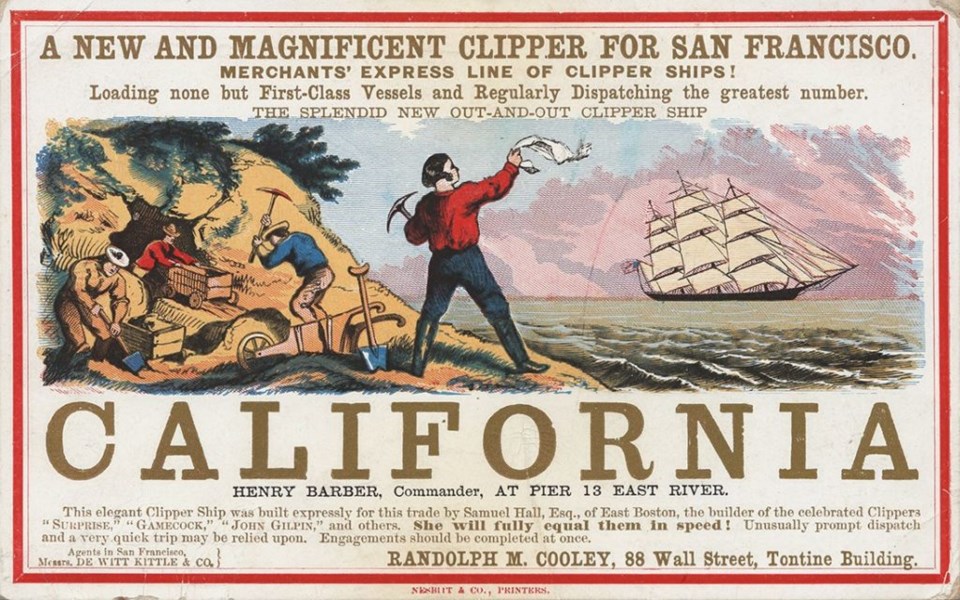

Clearly, there was money to be made in “mining the miners.” Although the interior reaches of California were hit particularly hard by the sudden outflow, for a time San Francisco profited from the mania. As the main point of departure for the new goldfields, San Francisco and its business community had substantial motivation to fuel the Fraser River Fever, and thus benefit through increased merchandising and transportation of gold seekers.

California was “‘knocked endways’ by this outrageous gold excitement.” Manton Marble in the New York-based Knickerbocker Magazine outlined the frenzied pace of change to his Eastern audience when he wrote:

During this brief period, ten steamers, making the round trip between San Francisco and Victoria in ten days, had been plying back and forth at their best speed, taking five hundred passengers and full freights up, with only thirty passengers and no freights down. Clipper-ships, and ships that were not clipper built, in scores, were crowded alike — the Custom-House sometimes clearing seven in a day. Many of the steamers and vessels went up with men huddled like sheep — so full that all could not sit or lie down together. . . . Nothing else was discussed in the prints, nothing else talked of on the street; all the merchants labelled their goods ‘for Fraser River:’ there were Fraser River clothes and Fraser River Hats, Fraser River shovels and crowbars, Fraser River tents and provisions, Fraser River clocks, watches, and fish- lines, and Fraser River bedsteads, literature, and soda-water. Nothing was saleable except it was labelled ‘Fraser River.’

Friends and family once considered lost were now presumed to have headed for the Fraser River. “On further inquiries about Richard Bullis, the man who mysteriously disappeared on last Friday,” the Bulletin snitched, “we learn that there are reports that he was suddenly taken with the Frazer river fever. . . . As nothing whatever has been learned of him direct, and as he was not exempt from the new contagion, it is probable that young Bullis is now rowing up towards Fort Hope.”

Indeed, the Fraser River had captured the imagination of California gold rush society. The San Francisco Newsletter peppered its pages with tantalizing stories of the new diggings: of William Price, “a boy who went fortune hunting,” and told of three men who had taken $1,800 in the short space of a month; or at Kerrison’s Bar where Saint Marie and Charles Hanna got four ounces in just half a day’s work with a rocker; or at Hill’s Bar, where men anxiously awaited quicksilver in order to accumulate $10 to $12 dollars a day, though predictions by old timers suggested the possibility of $50 to $100 to the hand; and Captain Daniels’ eyewitness account of a lone Frenchman having made the extraordinary pile of $10,000 in five quick weeks.”

The editor of the Bulletin declared: “What a tremendous effect will the news now going home have upon the people at the East and in Europe! Talk about $10, $20 and $50 per day to men who work for these sums a whole month or a year — why, if people get wild here [California], they will run mad there.”

People from every walk of life in San Francisco appeared to be leaving: “The Frazer Infection in the Police Department” sent officers Berham, Hanford, Quackenbush, Guyton, Riley, Dennison, Parks, Bovee, and Captain Donellan, flying north with the greatest of haste, while the “Dwindling of the Fire Department from Frazer Fever” was blamed on two hundred members of the force having bolted. James Moore, a member of No. 8 Fire Company (the “Pacific”) was one of the first Californians up the Fraser River, having taken part in the infamous Hill’s Bar strike. “Give my regards to all of ‘8’s’ fellows,” he wrote to a friend, having also sent a sample of Hill’s Bar gold from the $10 to $32 a day he had averaged while there.

Even the notorious Edward McGowan, narrowly escaping the long arm of Californian law, was said to have made “his stealthy exit” on the Sierra Nevada to the foreign gold mines.

While California “dominated the first decade of mining in the West,” states the American historian Duane Smith, “only a few small gold discoveries of local significance, primarily in Washington, Oregon, Arizona, and Nevada, [had] challenged this dominance. Then in the spring of 1858 came news of gold discoveries along the Fraser River in British Columbia.” Smith agrees that the Fraser River fever not only “swept San Francisco and the Mother Lode country,” but “perhaps more than 30,000 rushed to the new El Dorado; [though] we will never know the exact numbers.”

Smith is correct. There is absolutely no way to accurately determine just how many Californians flooded the Fraser and Thompson river corridors in 1858, but suffice to say that it was well in excess of the 30,000 – 33,000 people given as the usual conservative estimate.

With no colonial government established in New Caledonia, records of the myriad number of miners who chose to travel through the inland corridors of the Pacific Coast have undoubtedly been underestimated. We have been left records from the infamous and literate few, but what of the untold thousands of unknown miners who left no trace? Even many of those who chose to travel using maritime routes of communication are uncounted.

While larger steamships might provide passenger lists (though usually such ships sailed in excess of their recorded capacity), Smith rightly notes that other gold seekers “commandeered anything that would float” — presumably small-scale water craft that were also unrecorded.

For some Californians, it was not even the allure of mineral wealth as much as the sense of joining a rare human adventure of gold seekers who had grown accustomed to excitement.

And so, British Columbia – unlike any other province in the Canadian Confederation – was born of this wide-scale and sweeping mania – the British Columbia gold fever!

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Seven years before Confederation, the HMS Topaze arrived in Esquimalt, carrying a naturalist who would literally write the book on Vancouver Island flora and fauna.

- Daniel Marshall on the question of Indigenous Title...as it played out 160 years ago.

- Jody Vance on Vancouver's self-destructive policy of taxing the air above businesses.