The Williams Lake First Nation says it has located 93 potential human burials during the first phase of its search of the former St. Joseph’s Mission Residential School.

That brings to at least 1,401 the number of possible unmarked graves discovered at former residential school sites across Canada since the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc became the first to conduct such a search, announcing last spring the presence of 215 possible unmarked graves on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School.

“We understand that this information is going to be very difficult to process for survivors of St. Joseph’s Mission, their families, our community members and others in the general public,” Williams Lake First Nation Chief Willie Sellars said in a statement announcing the search results. “There is much more work to do on the St. Joseph’s site, and we have every intention of continuing with this work. For now, it’s important that everyone focus on their own wellness, and the wellness of those around them.

The truth is shocking but not surprising.

The National Truth and Reconciliation Commission lists the names of 4,130 children who died at residential schools on a student memorial register. The commission identified 1,953 of these children and another 1,242 who are known to have died at the schools but whose names are not known. In many cases, families were never informed. They were not even allowed the kindness of going home after death.

The commission warned upon the release of its report in 2015 that the number would climb as further information came to light. The commission estimated there are 400 burial sites across the country.

The commission’s memorial list has the names of 395 students who died at the 18 residential schools that operated in B.C. from 1867 to 1984.

That is likely a fraction of the true number, considering the commission lists 51 student deaths at the Kamloops school, less than a quarter of the 215 estimated graves there – so far.

The commission has confirmed 16 student deaths at St. Joseph’s near Williams Lake, including a boy who in 1920 ate poisonous water hemlock as part of a suicide pact with eight others desperate to escape the school by any means.

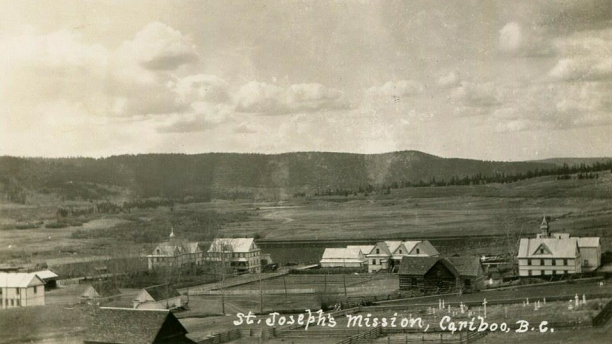

The Roman Catholic “school” operated on the outskirts of Williams Lake from 1891 to 1981, thousands of First Nations children attending over the decades from the dozens of Secwepemc, Tsilhqot’in, Stl’atl’imx, and Dakelh communities throughout the region and further afield. St. Joseph’s Mission closed its doors in 1981, the same year as the final death documented by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Over the following decades, four former staff of the school were convicted of sexual abuse charges, including Reverend Harold McIntee, Father Hubert O’Connor, Father Glenn Doughty and dorm supervisor Edward Gerald Fitzgerald. Several other investigations did not result in charges.

In his 2014 report to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Where Are The Children Buried, Lakehead University anthropologist Dr. Scott Hamilton found the estimates for the number of children who died at residential schools were likely low.

He cites the work of Dr. Peter Bryce, the chief medical officer for Indian Affairs in 1909 when he suggested there were 8,000 deaths per 100,000 students from all causes, including the deaths of students soon after leaving the schools in his calculations.

“Most of these children died far from home, and often without their families being adequately informed of the circumstances of death or the place of burial,” wrote Dr. Hamilton.

It is heartbreaking to read the list of names of children who died at B.C.’s residential schools, many of them not even afforded a last name, or the little girl who died on February 14, 1907, at St. Mary’s school in Mission, whose name on the list is “Mary Jane Indian.”

A National Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support to former students. The 24-Hour Crisis Line can be accessed at: 1-866-925-4419.

Dene Moore is an award-winning journalist and writer. A news editor and reporter for The Canadian Press news agency for 16 years, Moore is now a freelance journalist living in the South Cariboo.