Watching the raging wildfires of the British Columbia Interior these last months – ripping through the communities of Lytton, Logan Lake, Monte Lake, Paxton Valley, the Okanagan and beyond – has disturbed me greatly, the fast-moving trail of destruction has so outstripped the limited resources of the BC Wildfire Service.

Having spent many decades exploring the historical landscape of the BC Interior, these out-of-control fires are unprecedented, and yet BC is not alone with conflagrations having sparked up massively from the American states to the south and Siberia to the north.

The Interior was a fuse waiting to be lit for a long time, and so odd that beyond the valiant work of our firefighters, still there lacks a fulsome response by government. What the hell is going on here?

After much thought I decided last week to go see this sublime yet scorched country firsthand – the country I so love – and the worsening conditions of a province on fire.

Before departing last Saturday (14 August), I thought it best to contact my old friend Chris O’Connor, the former mayor of Lytton (2000 to 2008) and a retired professional forester.

The O’Connors’ lovely home, overlooking the confluence of the Fraser and Thompson rivers had been completely reduced to ashes – nothing remains of the house where I once stayed. Now Chris and his wife Denise (the former school principal in Lytton) are evacuees living in Merritt.

When I reached Chris on the phone, and after expressing my sincere condolences, I told him it had been difficult to get accurate information on the size and extent of these raging infernos. “Why don’t you come see for yourself,” implored O’Connor – and so I did!

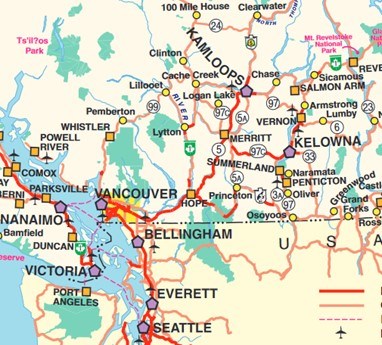

Traveling with my old friend John, a teacher with the Vancouver School Board, the journey across the Lower Mainland foretold what was to come. Thick smoke permeated the air along Highway No. 1 all the way to Hope, before we headed up through the historic gold rush towns of the Fraser Canyon: Yale, Boston Bar, and finally Lytton.

The highway was for the most part empty as we branched off to take the road down to Lytton, and see the destruction from a respectable distance.

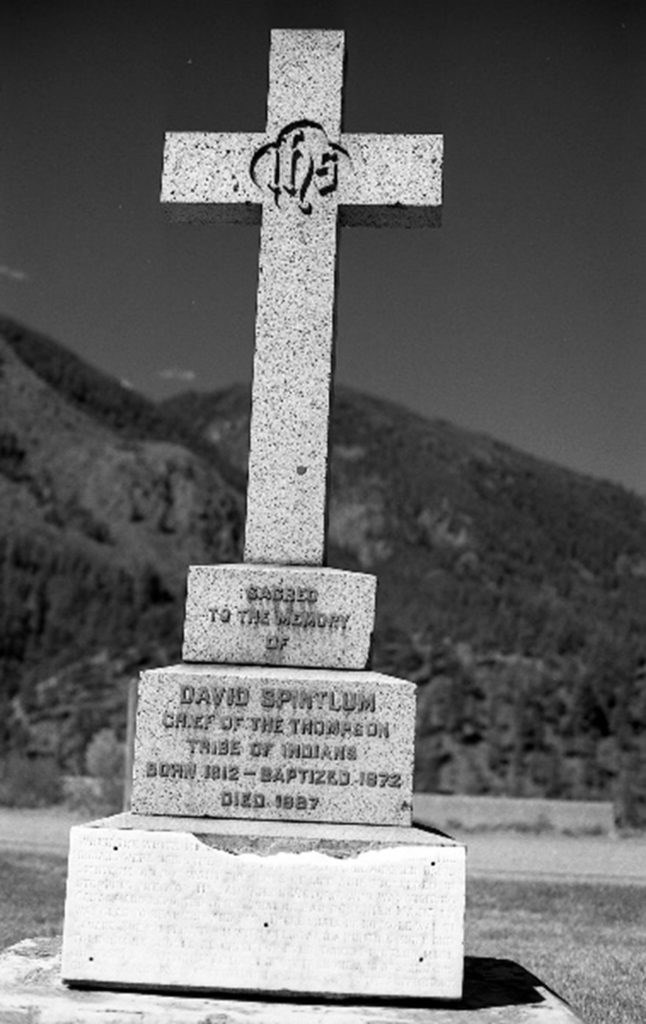

How utterly sad and disheartening, the old townsite looks like a war zone. Taking my binoculars in hand, I scanned the townsite looking for the O’Connor house. Sad to say, the only remaining object was a metal chair in the backyard where we once sat. I remember, we were discussing the Canyon War of 1858 and our early plans to eventually see the Chief David Spintlum (Cexpe’nthlEm) Memorial precinct revitalized in honour of the famous Indigenous peacemaker who was pivotal in ending the war of that year.

Remarkably, the Spintlum Memorial somehow remained unscathed by the Lytton Creek Fire that continues to rage. As of August 19, 852,386 hectares of BC have burned this year, or well in excess of an astounding two million acres!

By the time we reached Spences Bridge a half hour later, a further evacuation alert was issued for Lytton and further communities to the south. We made haste. Evidence of the Lytton Creek fire was everywhere: Jade Springs was gone; and the Skihist provincial campground torched, including portions of the historic Cariboo Waggon Road that passes through this park.

The thermometer had now reached about 36 degrees Celsius, the heat and heavy smoke enveloping us as we climbed the Thompson River to Spences Bridge, where I had arranged to meet friends John and Laurie Kingston, owners of the landmark Log Cabin Pub and adjacent motel.

Talk about hard times.

Following the coronavirus pandemic and earlier threats of fire to their community, the Log Cabin Pub had just reopened the week before, and business remained slow to nothing. Honestly, they looked like they had been through a war, exhausted, but delighted that we had chosen to come and stay the night.

That evening, while in the air-conditioned bar (a welcome respite indeed), I made occasional forays outside to examine the surrounding skyline. The BC Wildfire Service had made a firebreak on the opposite side of town, the eastern hills thoroughly scorched black. Apparently, as I heard from locals later that night, there was also the intention to blacken the hills on the west side of town, too, just above Highway No. 1, but the Spences Bridge community had not been in favour, fearing that would destroy the sturdy sage brush that assists in preventing mudslides.

As the evening continued, I noticed further smoke accumulating in the direction of Lytton farther down the Thompson River – an unsettling sight, made even more so by the news that Highway No. 8 (from Spences Bridge to Merritt) along the Nicola River was now closed, the Lower Nicola Valley having burst further into flames.

It was a tense and somewhat sleepless night as Spences Bridge remained on evacuation alert, and the volume of smoke continued to grow.

What were we to do now? We could not return via Highway No. 1, and now our expected route on No. 8 was closed. Plans can change quickly when traveling through wildfire zones. Nevertheless, we were determined to go see former Mayor O’Connor, and so next morning we headed in the direction of Kamloops as an alternate route to Merritt.

On the way we made a quick pit stop in Ashcroft and Cache Creek, noticing a number of businesses closed (including the historic Ashcroft Manor). Business was at a standstill, and I wondered how it could possibly get any worse for these already economically-stricken rural communities.

As we continued up the Trans-Canada Highway through Savona much of the journey was spent attempting to get the latest news of the extreme conditions – rather difficult at times to say the least – and knowing full well that weather reports were predicting not only high heat, but wind gusts that evening exceeding 70km per hour.

And then, the full gravity of our position could be seen on the far horizon.

Passing by the Cherry Creek Ranch, smoke continued to build, and the most shocking red-orange sky. It was 3:00 in the afternoon, and the heavens proceeded to turn black, as if nightfall.

We felt as if we had entered an apocalyptic land. Cherry Creek went on evacuation alert some hours later. It was almost as if the threat of fire was following us.

Next taking Highway No. 5 (Kamloops to Merritt) I decided it was time to call Chris O’Connor to get any updates he might have and arrange to meet. The Lower Nicola fire had now grown, and was on the move. While getting directions to his rental accommodation I inquired whether the Coquihalla was still open (thinking we might need a quick escape).

“For the moment,” came the reply.

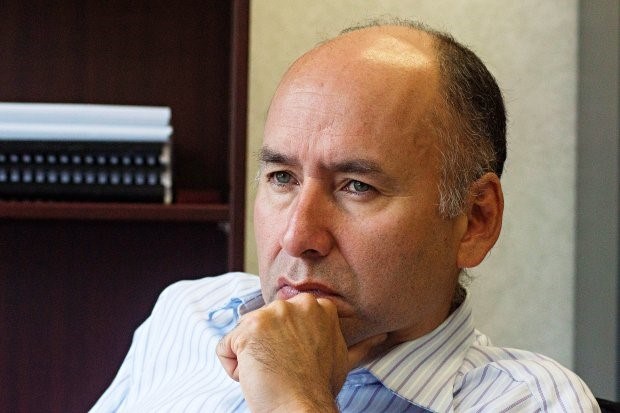

“Chris, the BC Wildfire Service seems far too stretched,” I exclaimed, “why does British Columbia not have a fleet of waterbombers to drench these things while they are still small?” In a rather remarkable coincidence, the ex-mayor replied, “Why don’t you come by earlier and meet Ellis Ross, MLA? He’s coming to my house before he speaks tonight at a public meeting. He’s got a lot to say about the subject.”

For the last many days Ross had been personally visiting many of the province’s hotspots in the BC Interior to see the destruction for himself: a whirlwind of activity that included Kamloops, Logan Lake, Monte Lake, and the Paxton Valley (among others) and now Merritt. As far as we could see, Ross seemed to be the only politician on the front lines, listening to the plight of ranchers and evacuees who had lost their homes and livelihoods.

Arriving in Merritt we had little time to check into our accommodations. While the sky behind the hotel gave the most ominous appearance, we privately felt we might have to forego our meetings if conditions became more extreme, and the Coquihalla was still open (at that time) if we needed to escape. We promptly left the hotel and made our way to the O’Connors’ place. It was wonderful to see them both, and Chris assured us we would be safe.

Ellis Ross, though late, finally arrived, direct from his extensive fact-finding mission of the previous few days. Ross spoke of the ranchers he had met who struggled to put out fires without any apparent assistance from the BC Wildfire Service, to evacuees who had lost their homes, and that he had visited as many of the disaster zones in rural communities as he could, often behind the lines.

What he discovered, he said, is that BC is not only in a lamentable state, but that the whole provincial approach to snuffing out fires requires serious re-examination and effective and immediate change. I liked his straightforward talk, he certainly was not beating about the bush, committing to founding a $78 million firefighting institute in BC.

As we departed for Ross’s public speech, the predicted high winds had commenced. I spent much of the evening chasing my broad-rimmed hat, swept away on multiple occasions by huge gusts of hot dry wind.

Quite frankly, it was surprising that anyone would have come out under the risk of the escalating conditions – including Ellis Ross himself. There were about 20 or 30 brave souls out to meet him, including former Lieutenant-Governor Judith Guichon.

With the winds howling outside, Ross again spoke of the crisis occurring in British Columbia and the shame of a province ill-equipped to stamp out small fires before they became infernos. He spoke with confidence, but you could also see the humility of one who had seen the sprawling devastation. Again, the only politician I’ve seen with the courage to leave the coast and immerse himself fully into the fire battlefield. I found that both courageous and admirable.

Unfortunately, time for questions came to an abrupt halt. One of the organizers crept towards Ross to whisper in his ear. Right then and there, it was announced that Merritt was now on evacuation alert! The meeting was over, and the crowd quickly dispersed.

While Ross and his campaign team immediately left for Kamloops, I now found myself outside the hotel with my traveling companion John and Chris O’Connor. Looking south towards July Mountain, the evening horizon was ablaze, the wind increasing, and the Coquihalla was now closed with massive fires on both sides of the highway having merged.

What the hell were we to do now? Of course, as recommended we consulted Drive BC. But the system was down. Bloody great! Who’s running this show? Should we stay or should we go now?

O’Connor, who had seen it all before, simply said, “Looks like you might have to take the highway through Princeton tomorrow and the No. 3 back to Hope.” Indeed, we would. That was now the only way out.

A certain degree of pandemonium then set in: restaurants quickly closing, further evacuees streaming in from the Lower Nicola and the Okanagan fires to join the Lytton refugees from the previous month. We saw tearful police officers in one of the hotel lobbies, as the feeling of apocalypse and confusion permeated the air. Merritt soon announced that no one should further evacuate to their city. They were full.

With Drive BC out of commission my friend John and I continued to find the best updates on a variety of Facebook sites. That’s how we next learned the Lytton fire had now crossed the mountain at Spences Bridge where we had been earlier in the day (helicopters were employed immediately to douse the flames), and to top it all off, three separate mudslides had also occurred since our departure – two along Highway No. 1 between Lytton and Spences Bridge, and one on the Highway from Lytton to Lillooet.

Soon, far away Lillooet was also back on evacuation alert. Would the Duffy Lake Road from Lillooet to Pemberton also be shut down, we wondered? Throughout there was the inescapable feeling that we were surrounded on all sides by fire.

Thankfully, after another fitful night’s sleep, we made our way from Merritt to Princeton – the traffic was intense, compounded by a vehicle accident and, oddly enough, road-paving crews laying asphalt on our only way out!

Nevertheless, we made it to a chaotic Princeton, left to itself to deal with the overload in traffic flowing from the fires of the Okanagan. We joined the long line and headed home through further extreme smoke all the way to Hope. What a trip!

I think it is high time the BC Wildfire Service be given the additional resources they so desperately need. And after my three-day flurry through the wildfire lands of the BC Interior, I would go one further: it’s time this province gave serious attention to the increasing risk of future and greater wildfire activity in the coming years. Why does BC not have its own waterbomber fleet?

I am no expert, but the Super Scooper waterbomber is not only made in Canada, but deployed around the world – why not BC? The experience of this high heat, drought-ridden summer suggests we need to hit these big fires hard while they remain small.

What is the hope for British Columbia? How many more small towns must be lost before the seeming indifference of our major urban populations wake up to the larger cost of what is occurring right now?

There is in this province a disgraceful disconnect within an ever-growing urban-rural divide. Will my friend Chris O’Connor see his town rebuilt? And will the Lytton First Nation see Kumsheen (Lytton) rise from the ashes? Chief Spintlum’s monument still stands, but where do we?

So, I have to ask – is anyone listening? Yes, there is someone – and he is a quite remarkable leader I met last weekend, by the name of Ellis Ross.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall last shared his reflections on BC Day, truth, and reconciliation.

- The first job of leadership is showing up, telling people the latest, and how you have their backs, says Drex. But as much of BC burns, unfortunately John Horgan hasn’t shown up.

- From horse people to lemonade stands, Dene Moore thanks those who have stepped up to help those affected by wildfires.